He kōrero whaitake mō te āheitanga

Capability descriptions

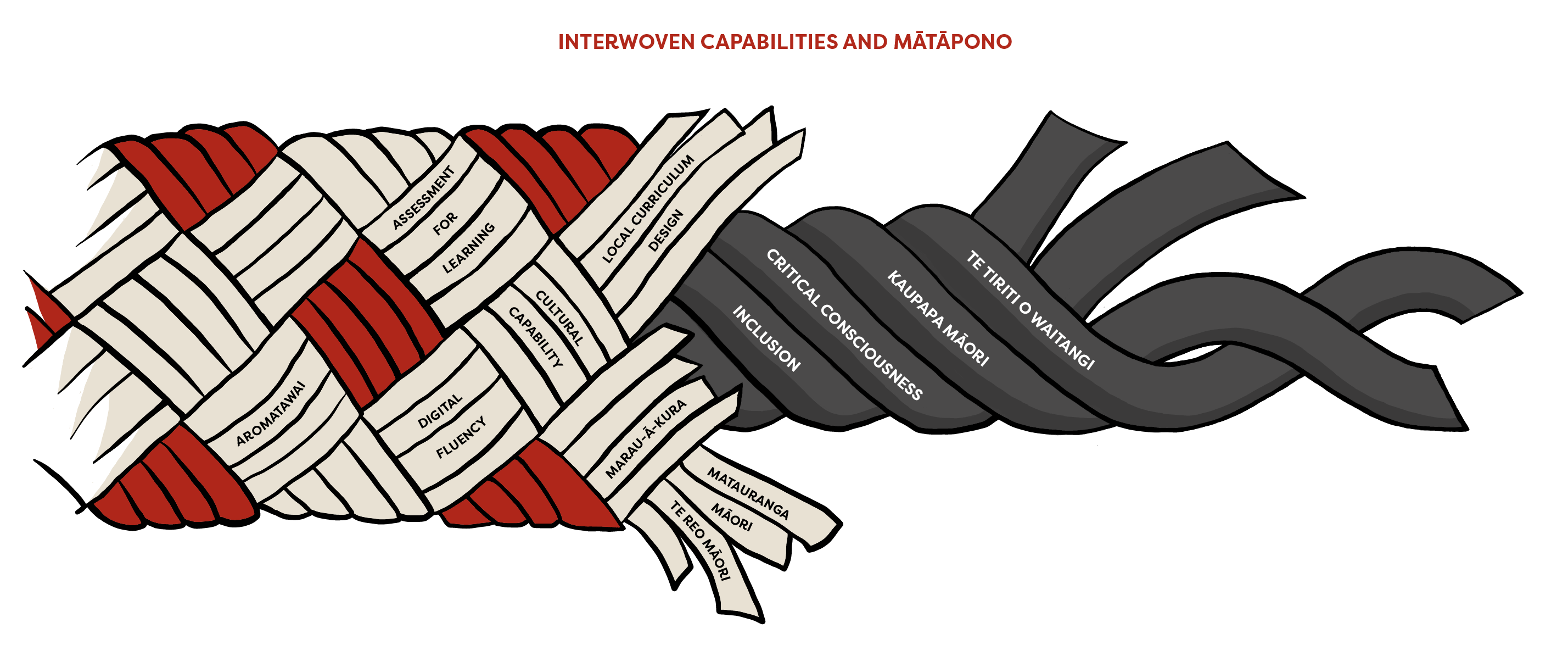

Ngā hua o te mahi tahi | Collective impact

We all have different levels of familiarity with the four prioritised capabilities and differing understandings of what they mean. Now we look at them anew, describing them as woven around the kaupapa and the four mātāpono.

These capability descriptions are intended to reframe our thinking about the knowledge and skills required to make them part of our everyday ways of thinking, feeling, and doing.

The following capability descriptions are in two parts:

- A summary of how we may have previously understood the capability.

- What the kaupapa means for how the capabilities may be understood and enacted.

Reframing our thinking about the capabilities will require adaptive expertise as defined in the ERO’s evaluation indicators:

Adaptive expertise is a fundamentally different way of conceptualising what it means to be a professional. Its defining characteristic is the ability to respond flexibly in complex contexts: Adaptive experts know when students are not learning, know where to go next, can adapt resources and strategies to help students meet worthwhile learning intentions, and can recreate or alter the classroom climate to attain these learning goals.

Download a copy of PLANZ interwoven capabilities

Te whakahoahoa ki te marau | Local curriculum design

Local curriculum design is a way of recognising that all ākonga are part of their community, and orientates relationships and learning around those communities.

Our current understandings

Together, The New Zealand Curriculum (NZC), Te Marautanga o Aotearoa, and Te Whāriki make up the National Curriculum. These three documents set out the learning entitlements of ākonga in our early learning contexts, schools, and kura.

The National Curriculum establishes the knowledge, competencies, and values ākonga need to flourish as citizens of Aotearoa New Zealand, along with the progress and expectations associated with this learning.

School and kura curriculum (both referred to as local curriculum) is designed by schools and kura in partnership with ākonga, whānau, hapū, iwi, and other community members for their learners and in their place. Local curriculum includes opportunities for ākonga to learn within their communities and to contribute in ways that build on and strengthen both community and ākonga capabilities. This requires critical thinking about what matters to ākonga, their whānau and communities, and what is worth learning.

A well-designed local curriculum offers rich learning opportunities, and strengthens partnerships with mana whenua, hapū, iwi, and community. Ākonga deepen their knowledge of the world through exploring new contexts that can be found at local, regional, national, or international levels. They learn to work with people who have different perspectives, and develop the competencies of active, responsible, and engaged citizens. They are able to construct learning pathways across time and different learning contexts.

Mānenehia te taura | Tightening the taura

The kaupapa pushes us to transformation by reconsidering:

- partnerships

- equity

- the purpose of learning

- the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and learning outcomes that we value.

Upholding mana ōrite, returning rangatiratanga, and ensuring mana-enhancing experiences for all tamariki-mokopuna and whānau requires us to re-vision our approaches to both the design and content of local curriculum.

Relationships are at the heart of local curriculum design. Tumuaki and kaiako will know tamariki-mokopuna and whānau well, and create opportunities for them to have greater control over learning at school. Kaiako will recognise, value, and build upon the cultural capital they bring.

At the same time, ākonga, whānau, hapū, iwi, mana whenua, and others in the community will be asked to define their aspirations and contribute their knowledge, expertise, and insights. This is how Te Tiriti o Waitangi can be actualised and mana ōrite upheld for both partners.

Kaiako and tumuaki who identify as designers of curriculum do not control the learning, but use their expertise to activate (Hattie, 2012) or enable it (Fullan & Donnelly, 2013). They integrate local aspirations with the entitlements set out in the National Curriculum to create rich learning opportunities that give all ākonga the opportunity to progress along meaningful personalised pathways.

Read more about: Local curriculum design

Āheitanga ahurea | Cultural capability

Cultural capability is knowing, valuing, and integrating the cultural capital of all ākonga into learning.

Our current understandings

We all have cultural capital: shared values, beliefs, and ways of knowing and being. Our cultural capital includes our language and our preferred ways of communicating and relating to others. The term “capital” links to the idea of wealth – our language and culture are our strengths. People who are culturally capable feel confident in their own identity while recognising and valuing other people’s language and culture.

Culture is not just about ethnicity – there are many other dimensions, including those of work, family, organisations, sexuality, and disability. Culture can connect people across all these dimensions.

In education, cultural capability begins with valuing the cultural capital of all tamariki-mokopuna and making it the lever for their success. This involves understanding the cultural and linguistic capital of tamariki-mokopuna and integrating these resources into their learning at school. For this to happen, kaiako and tumuaki engage in culturally responsive learning partnerships that exemplify ako. These partnerships ensure ākonga, whānau, iwi, mana whenua, and others in the community feel they belong at their local school and that they have a part to play in constructing a local curriculum in which they can see themselves.

Cultural capability requires a range of cultural competencies, including those described in Tātaiako and Tāpasa, and in our descriptions of inclusive practice.

Mānenehia te taura | Tightening the taura

The kaupapa pushes us to go further. We must understand the bicultural constitutional foundation of our nation established in Te Tiriti o Waitangi and its recognition of tangata whenua (the first people of this land) and tangata tiriti (the people who came later). Tangata tiriti are not asked to lose their own identity and be Māori, but are asked to discover what is required to return rangatiratanga and ensure ākonga Māori experience educational success as Māori. Educators must truly know and partner with the tamariki-mokopuna and whānau they serve. Cultural capability under this kaupapa also involves critical consciousness and understanding the principles and practices of kaupapa Māori and inclusion. It begins with self-awareness. Understanding and being aware of our own culture enables us to understand, recognise, and respond to other people’s culture.

As people grow in cultural capability and critical consciousness, they ask questions about the institutional culture that has discriminated against some groups, and they take action to resist. They adopt kaupapa Māori and inclusive teaching pedagogies that foster mana-enhancing experiences for all tamariki-mokopuna and whānau.

Read more about: Cultural capability

Aromatawai | Assessment for learning

Assessment for learning offers ākonga ways of understanding their own growth and learning, and informs further learning. When it is founded on ngā matapono, assessment for learning will challenge what we value as important for learning and how we assess it.

Our current understandings

Assessment for learning refers to the understanding that the core purpose of the assessment of ākonga learning is to support further learning. Teaching, learning, and assessment are inextricably linked.

Assessment for learning has enormous potential to contribute to educational improvement. Kaiako who are good at assessment for learning actively grow their pedagogical, disciplinary, and assessment knowledge. At the same time, they grow their knowledge of and relationships with ākonga, and their understandings about curriculum and progress. They use their knowledge to notice and recognise the needs, strengths, progress and interests of ākonga so that they can make defensible decisions about what to do next. They select pedagogical approaches that are explorative and in which ākonga themselves are resources for learning. They are explicit about what is taught and why, and they co-construct the definitions of success with ākonga.

In learning contexts where assessment for learning practices are in place, ākonga and whānau can talk confidently about what is being learned, and why. They take part in conversations about ākonga progress, their contribution to that progress, and the next steps for learning.

Mānenehia te taura | Tightening the taura

The kaupapa pushes us to consider who does the assessing and what is assessed. Everybody in the learning community should be asking whether the local curriculum is offering the rich learning opportunities that will empower ākonga to succeed. Assessment for learning practices will be mana-enhancing for tamariki-mokopuna and their whānau. They will foster agency and support the construction of meaningful learning pathways that return rangatiratanga and open the way to new possibilities.

Realising the kaupapa would mean that ākonga and whānau become active participants in critical conversations about what is being learned, and why. They would know how curriculum learning connects to their lives, how they contribute to learning interactions, and how their learning applies to other contexts. Ākonga and whānau would know how they are going and the next steps for learning along individualised and coherent learning pathways.

Read more about: Assessment for learning

Matatauranga ā-matihiko | Digital fluency

When underpinned by ngā mātāpono, digital fluency includes empowering ākonga to be conscious users and creators of digital technology, and offers them contexts for understanding how digital technology relates to their lives.

Our current understandings

Digital fluency includes capabilities to effectively and ethically access and interpret information; discover meaning and construct knowledge; design, develop and curate content; and communicate ideas. People demonstrate digital fluency when they can act independently and make free choices within a digitally connected world.

The term "digital fluency" is contested. However, the adaptation of the National Curriculum to include hangarau matahiko, and digital technologies, reflects the recognition that digital fluency is now an essential capability for living and lifelong learning. It enables people to participate in life-enhancing opportunities (social, economic, cultural, and civil) and achieve goals that are important to them and to others. This can only happen if digital technology is integrated across the curriculum.

Mānenehia te taura | Tightening the taura

Many educators have been rapid adopters of digital technology, but digital fluency is not yet being demonstrated in all learning contexts. It is not enough to bring new technologies into the learning context, their effective use requires new pedagogies for deep learning. Learning partnerships and learning connections are an integral part of daily practice to realise the potential of digital tools and resources.

The kaupapa connects well with recent thinking about how digital fluency can foster digital citizenship. A digital citizen is “someone who can fluently combine digital skills, knowledge and attitudes in order to participate in society as an active, connected, lifelong learner” (Netsafe, 2018, page 6).

Digital citizenship requires us to be critically aware that we are all part of something bigger than ourselves. Digital citizens question the wider impacts of technology, locally, nationally, and globally and take responsibility for how their own use (or misuse) of digital technologies affects other people and the environment. They understand digital technology as just one tool for achieving their goals, and that it may not always be the best one. If tumuaki and kaiako foster these understandings and dispositions for themselves they will then be able to share them with tamariki-mokopuna. This is deep learning that can be undertaken alongside and in partnership with all the learners in any school community.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, any consideration of citizenship includes thinking about Te Tiriti and what that entails. Kaupapa Māori invites us to take a critical and ethical view on the use of technology to create information, and how technology use can embed the tikanga and values of te reo Māori. The digital citizenship model also broadens opportunities to include people who are currently excluded from full participation in society, including tāngata whaikaha.

Conscious acts of teaching and leadership are required to ensure digital technology promotes greater inclusion for all. How might it help all tamariki-mokopuna participate actively and productively in their whānau, communities, and the wider world? How might kaiako encourage critical thinking in tamariki-mokopuna so that progress is not just something that happens to them?

Read more about: Digital fluency